Wattasid Dynasty

Morocco Under the Wattasid Rule

Morocco endured a prolonged multifaceted crisis in the 15th and early 16th brought about by economic, political, social and cultural issues. Population growth remained stagnant and traditional commerce with black Africa cut off as the Portuguese occupied all ports. At the same time, towns were impoverished and intellectual life on the decline.

Morocco was in decline when the Berber Wattasid dynasty assumed power. While the previous rulers, the Merinid, tried to repel the Portuguese and Spanish invasions and help the kingdom of Granada to outlive the Reconquista, the Wattasids accumulated power through political maneuvering. When the Merinids became aware of the extent of the conspiracy, they slaughtered the Wattasids, leaving only Abu Abdellah al-Shaykh Muhammad ben Yehya alive. He went on to found the Kingdom of Fez and establish the dynasty to be succeeded by his son, Mohammed al-Burtuqali, in 1504.

The Wattasid rulers failed in their promise to protect Morocco from foreign incursions and the Portuguese increased their presence on Morocco’s coast. Mohammad al-Chaykh’s son attempted to capture Assilah and Tangiers in 1508, 1511 and 1515, but without success.

In the south, a new dynasty arose: the Saadians who seized Marrakesh in 1524 and made it their capital. By 1537 the Saadians were in the ascendent when they defeated the Portuguese at Agadir. Their military successes contrast with the Wattasid policy of conciliation towards the Catholic kings to the north.

As a result the people of Morocco tended to regard the Saadians as heroes, making it easier for them to retake the Portuguese strongholds on the coast, including Tangiers, Ceuta and Mazagan. The Saadians also attacked the Watttasids who were forced to yield to the new power. In 1554, as Wattasid towns surrendered, the Wattasid sultan, Abou Hasan Ali, briefly retook Fez. The Saadians quickly settled the matter by killing him and, as the last Wattasids fled Morocco by ship, they too were murdered by pirates.

The Wattasid did little to improve general conditions in Morocco following the Reconquista. It was necessary to wait for the Saadians for order to be reestablished and the expansionist ambitions of the kingdoms of the Iberian peninsula to be curbed.

The Wattasids were finally supplanted in 1554, after the Battle of Tadla, by the Saadi princes of Tagmadert who ruled all the South of Morocco since 1511.

Morocco under the Saadi Dynasty

Extent of the Saadian empire during the reign of Ahmad al-Mansur

The early rise of sharifism in Fez took place again under the Marinids (1269-1465), with the Idrissids still playing an important role and with a pronounced mythical dimension that was symbolized by the miraculous discovery of the body of Moulay Idriss in Fez and the extension of his sanctuary. The Battle of the “Wadi al-Makhazin”, also known as “Battle of Three Kings” marked the Marinid Dynasty. “Wadi al-Makhazin” was a major battle fought in northern Morocco, near the town of Ksar-el-Kebir between Tangier and Fez, on August 1578, between the Moroccans and the Christians (Portuguese, Spanish, Italian and German) under King Sebastian who attacked northern Morocco with 125.000 men and 200 cannons. They wanted to occupy Morocco and christianise it as they have done with Andalusia. The combatants were the army of the King Sebastian of Portugal and the Moroccan army nominally under Abd Al-Malik Saadi. The militantly Christian king had planned a crusade after al-Mutawakkil asked king Sebastian to help him recover his throne, which his uncle Abd Al-Malik had taken from him. Sebastian wished to subject Muslim Morocco to Christian rule. Allied with the deposed Moroccan sultan, al-Mutawakkil, he landed at Tangier weighed down by much artillery and an army of 20,000 men. At the Wadi al-Makhazin near Ksar el-Kebir, between the Loukkos River and one of its tributaries, Sebastian struck at Abd al-Malik and his brother Ahmed. The Muslim forces, though not as well equipped as the Portuguese, numbered 50,000 men—infantry and cavalry. They forced the Christians to retreat to Larache on the coast, but, in crossing the Wadi al-Makhazin, which was then at high tide, many drowned or surrendered. Both Sebastian and al-Mutawakkil were drowned, and Abd al-Malik, seriously ill from the beginning of the encounter, died during the battle —hence the name of the battle. The victory provided the Muslim soldiery with a rich booty and the country with a new sultan, Ahmad, now known as Ahmed al-Mansur Dahbi (Ahmed the Victorious the Golden); it gave Morocco a new prestige in Europe, furthering its diplomatic and commercial status. The death of the young Sebastian without heir, on the other hand, brought the Portuguese empire under Spanish control for the next 60 years.

Shaykh Sidi Mohammed Sharqi al-Umari ( d. 1595) was the Qutb of the Time. Hence Shaykhs of the orders participated in the battle. Shaykh Abul Mahasin al-Fasi of the Shadhiliya order has himself attended Wad al-Makhazin along with the Jazulite masters Sidi Abdellah Benhassoun (d. 1598) and Sidi Mhammed ibn Ali ibn Raysun (d. 1603), which took place in 1571. We want to mention here the three positions of Sidi Abul Mahasin al-Fasi during and after the battle. The first position was when people were alarmed by the army of the Portuguese which was occupying Moroccan lands, and which had almost reached al-Qasr all-Kabir, the birthplace of Shaykh Abul Mahasin. People decided to leave the land and flee to the mountains since the Sultan of Morocco was still in Marrakech about 100 kilometres from there. Shaykh Sidi Abul Mahasin spoke to people and encouraged them to remain firm. He said: “Stay in your towns and homes. The King of the Christians is confined where he is until the Sultan comes from Marrakech’. The Christians will be booty for the Muslims. Whoever wishes will be able to receive 50 uqiyyas for each Christian,” indicating their price. The second position was during the battle itself. We read in Ahmed ibn Khalid Nasiri’s (d. 1897) Kitab al-Istiqsa, “On that day Shaykh Abul Mahasin was in one of the flanks. I think that there was some movement by the Muslim army and there was a break on that side. The Muslim lines broke and the Christians attacked them, but the Shaykh stood firm as did those with him until Allah give victory to the Muslims.” The third position was when Shaykh Abul Mahasin was present on an expedition in which he fought, but refrained from the booty, not taking any of it because it was looted and not taken in legal manner due to the death of the Sultan that day.

Ahmed al-Mansour Dahbi ruled the Saadi dynasty from 1578 to his death in 1603, the sixth and most famous of all rulers of the Saadis. He was the third son of Mohammed Shaykh (d. 1505) who had seized Fez from the Idrissids in 1471. Ahmed al-Mansur was an important figure in both Europe and Africa in the sixteenth century, his powerful army and strategic location made him an important power player in the late renaissance period. Al-Mansur began his reign by leveraging his dominant position with the vanquished Portuguese during prisoner ransom talks, the collection of which filled the Moroccan royal coffers. Morocco’s standing with the Christian states was still in flux. Ahmed al-Mansur developed friendly relations with England in view of an Anglo-Moroccan alliance. In 1600 he sent his Secretary Abdelwahid ibn Masoud as ambassador to the Court of Queen Elizabeth I of England to negotiate an alliance against Spain. But al-Mansur knew that the only way his regime would survive was to continue to benefit from alliances with the Christian economic powers. To do that Morocco had to control sizable gold resources of its own. Accordingly, al-Mansur was drawn irresistibly to the trans-Saharan gold trade of the Songhai. The Songhai Empire, was a pre-colonial African state centered in eastern Mali. From the early 15th to the late 16th century, it was one of the largest African empires in history. On October 16, 1590, Ahmed took advantage of recent civil strife in the empire and dispatched an army of 4,000 men across the Sahara desert under the command of converted Spaniard Judar Pasha. Though the Songhai met them at the Battle of Tondibi with a force of 40,000, they lacked the Moroccan gunpowder weapons and quickly fled. Ahmed advanced, sacking the Songhai cities of Timbuktu and Djenné, as well as the capital Gao. Despite these initial successes, the logistics of controlling a territory across the Sahara soon grew too difficult, and the Saadians lost control of the cities not long after 1603. The absence of the restraining force of the state of Songhay meant a free-for-all situation, with various groups vying for control. The nomads, especially the Tuaregs, seemed to have had a field day, ceaselessly harassing the settled groups, creating an atmosphere of insecurity and uncertainty. Predictably this situation affected trade and caused movements and dislocation of peoples. It was to continue until the emergence of the Qadiri Sufi Shaykh, Sidi Mukhtar al-Kunti (1729-1811), about the mid eighteenth century.

From 1603–1627 a civil war took place after the death of Ahmad al-Mansur, opposing three pretenders : Abou Fares Abdallah, Abou Fares Abdallah and Mohammed esh Sheikh el Mamun ; it was beginning of the decline of the Saadi Empire. In 1628, the reunification of Fes and Marrakech saw its ending, but Saadians didn’t retrieve the control over many territories : Rabat, Salé and Tetouan ruled by Andalusis, Tafilalet by the Alaouites, Oujda by the Ottomans and many other territories lost to warlords, Zaouias leaders and refractory tribes ; they lost gradually the control over the territories that remained under their rule until 1659, when they disappeared from the Moroccan political and military scenes.

Flag of Saadi dynasty , used along with a white banner

The Alawids – The Last Dynasty

A different map of Morocco (Yellow) with Spanish Rio de Oro (Purple) and French Algeria (Red), 1890.

According to tradition, the Alaouites entered Morocco at the end of the 13th century when Al Hassan Addakhil, who lived then in the town of Yanbu in the Hejaz, was brought to Morocco by the inhabitants of Tafilalet to be their imām. They were hoping that, as he was a descendant of Muhammad, his presence would help to improve their date palm crops thanks to his barakah “blessing”, an Arabic term meaning a sense of divine presence or charisma. His descendants began to increase their power in southern Morocco after the death of the Saʻdī ruler Ahmad al-Mansur (1578–1603). In 1669, the last Saʻdī sultan was overthrown in the conquest of Marrakesh by Mulay r-Rshid (1664–1672). After the victory over the zāwiya of Dila, who controlled northern Morocco, he was able to unite and pacify the country.

The organization of the sultanate developed under Ismail Ibn Sharif (1672–1727), who, against the opposition of local tribes began to create a unified state. Because the Alaouites had difficult relations with many of the country’s Berber and Bedouin-Arab tribes, Isma’īl formed a new army of black slaves, the Black Guard. However, the unity of Morocco did not survive his death—in the ensuing power struggles the tribes became a political and military force once again.

Sultan Moulay Ismail (d. 1727), the second king of the Alawite dynasty and founder of the city of Meknes, extended the borders of the Moroccan empire south to Mauritania, during which it is often reported that during his reign a woman or a Jew could travel alone from the farthest south of the country to its farthest north without being in fear about his safety. His long reign (1672-1727) saw the consolidation of Alawi power and the development of an effective army trained in professional military techniques. In 1672, with the sudden death of his half brother, Mawlay Rashid, founder of the dynasty, Sultan Ismail, then acting viceroy in Fez, immediately seized the treasury and had himself proclaimed ruler. His claim was challenged by three rivals–a brother, a nephew, and al-Khidr Ghilan, a tribal leader of northern Morocco. These rivals were supported by the Ottomans, acting through Algiers, who hoped to weaken the Alawis by supporting internal subversion so that they could extend their rule over Morocco. As a result, relations with the Ottoman regent of Algiers were strained throughout Sultan Ismail’s reign. The succession war lasted five years. Al-Khidr Ghilan was defeated and killed in September 1673, but Sultan Ismail had greater difficulties with the brother and nephew. He finally included them in the Moroccan power structure by recognizing them as semi-independent governors of important provinces. He completed the internal pacification of Morocco in 1686 with the final defeat and death of his nephew Ahmad ibn Mahraz.

In 1673 Sultan Ismail created the ‘Abid al-Bukhari, or slaves of Bukhari, who gained fame by this title for swearing allegiance to the Sultan on the Sahih of Imam Bukhari. The ‘Abid al-Bukhari army made up of slaves bought from their masters and enlisted into this army together with freeborn blacks. The contingent was provided with women, and the offspring of these unions were entered into special schools and given specialized military training. Toward the end of his reign he had a black army of more than 150,000 men, of whom about 70,000 were kept as a strategic reserve in and around Meknès. His army was equipped with European arms, and his officers learned to combine artillery with infantry effectively. He used these forces against the Ottomans in Algiers in the years 1679, 1682, and 1695/96 in expeditions designed to pacify his frontiers and to punish the regent of Algiers. In the end the Ottomans agreed to respect Moroccan independence. Mawlay Ismail’s relations with the European powers were much more complex. He hated the Europeans as infidels, yet needed them as suppliers of arms and other finished products. Throughout his reign there was intermittent warfare with the European settlers of the Moroccan seaports: in 483/1091 he captured Mamora Forest from the Spanish, and in 1684 he expelled the English from Tangier. In order to challenge Spain for possession of its settlements within Morocco, he became increasingly friendly with Louis XIV of France, the enemy of Spain. France was to reap great commercial benefits from this friendship. French influence became paramount in Morocco; French officers trained Moroccan artillerymen and helped in the building of public works. The palace of Meknès, styled on that of Versailles, was a massive monument to Ismail’s will and determination.

After Moulay Ismaïl’s death at the age of eighty (or around ninety by the 1634 birthdate) in 1727, there was another succession battle between his surviving sons. His successors continued with his building program, but in 1755 the huge palace compound at Meknes was severely damaged by an earthquake. Only with Muhammad III (1757–1790) could the kingdom be pacified again and the administration reorganized. A renewed attempt at centralization was abandoned and the tribes allowed to preserve their autonomy. Under Abderrahmane (1822–1859) Morocco fell under the influence of the European powers. When Morocco supported the Algerian independence movement of the Emir Abd al-Qadir, it was heavily defeated by the French in 1844 at the Battle of Isly and made to abandon its support.

From Muhammad IV (1859–1873) and Hassan I (1873–1894) the Alaouites tried to foster trading links, above all with European countries and the United States. The army and administration were also modernised, to improve control over the Berber and Bedouin tribes. With the war against Spain (1859–1860) came direct involvement in European affairs—although the independence of Morocco was guaranteed in the Conference of Madrid (1880), the French gained ever greater influence. German attempts to counter this growing influence led to the First Moroccan Crisis of 1905-1906 and the Second Moroccan Crisis (1911). Eventually the Moroccans were forced to recognise the French Protectorate through the Treaty of Fez, signed on December 3, 1912. At the same time the Rif area of northern Morocco submitted to Spain.

Under the protectorate (1912–1956), the infrastructure was invested in heavily in order to link the cities of the Atlantic coast to the hinterland, thus creating a single economic area for Morocco. However the regime faced the opposition of the tribes—when the Berbers were required to come under the jurisdiction of French courts in 1930 it marked the beginning of the independence movement. In 1944, the independence party Istiqlāl was founded, supported by the Sultan Muhammad V (1927–1961). France was obliged to grant Morocco independence on March 2, 1956, leaving behind both a legacy of urbanization and industrial economy in some cities, and destruction and isolation in the areas that hosted the Berber resistance against France and Spain between 1912 and 1933.

Moroccan-Portuguese conflicts

Ksar-el-Kebir battle, also known as the battle of the 3 kings

Moroccan-Portuguese conflicts refer to a series of battles between Morocco and Portugal throughout history. The first battle was in Ceuta, marking the start of the Portuguese Empire. The last battle was at Ksar-el-Kebir, initiating the 1580 Portuguese succession crisis. This resulted in a dynastic union between the Kingdom of Portugal and the Kingdom of Spain.

Barbary Wars

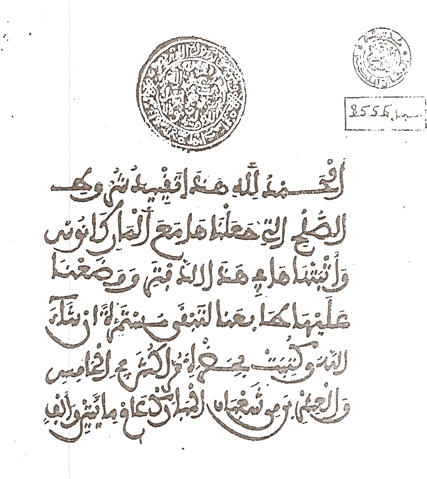

First part of US/Moroccan 1787 Treaty of Peace & Friendship in its original form in Arabic.

Though Morocco was not part of the Ottoman empire, Moroccan pirates held their activities in both the Mediterranean sea and the Atlantic ocean. They used two main ports as bases; Salé and Tétouan. Salé pirates roamed the seas as far as the shores of the Americas, bringing back loot and slaves. The character Robinson Crusoe, in Daniel Defoe’s novel by the same name, sailed off from the mouth of the Bou Regreg river.

In 1783 the United States made peace with and was recognized by Great Britain, and in 1784 the first American ship was captured by pirates from Morocco. The stars and stripes was a new flag to them. After six months of negotiation, a treaty of friendship between the U.S. and Morocco was signed, $60,000 cash was paid, and trade began. Morocco was the first independent nation to recognize the United States back in 1778.

First Fanco-Moroccan War

Battle of Isly (1844)

The Franco-Moroccan War (1844) was a series of conflicts fought between France and the Saadi sultanate of Morocco. The principal cause of war was the retreat of Algerian resistance leader `Abd al-Qādir into Morocco following French victories over many of his tribal supporters during the French conquest of Algeria.

Abd Al-Qādir had begun using northeastern Morocco as a refuge and a recruiting base as early as 1840, and French military movements against him heightened border tensions at that time. France made repeated diplomatic demands to Sultan Abd al-Rahman to stop Moroccan support for Abd al-Qādir, but political divisions within the sultanate made this virtually impossible.

Tensions were heightened in 1843, when French forces chased a column of Abd al-Qādir supporters deep into Morocco. These men included Alawī tribesmen from Morocco, and French authorities interpreted their actions as a de facto declaration of war. While they did not act immediately, French military authorities threatened to march into the sultanate if support for Abd al-Qādir was not withdrawn, and the border between Algeria and Morocco properly demarcated so that defenses against future incursions could be set up.

By early 1844 French troops had constructed a fortification at Lalla-Maghnia, the site of a Muslim shrine near Oujda, and clearly not within territory traditionally claimed by the Ottoman Regency of Algiers. An attempt to dislodge these troops peacefully in late May 1844 failed when Alawī tribal fighters fired on the French and were eventually driven back to Oujda. Rumors surrounding this incident (including reports that the shrine had been defiled and that French troops had entered Oujda and hanged to governor) fanned the flames of jihad in Morocco. Amid escalating troop buildups and skirmishes in the frontier area, French Marshal Thomas Robert Bugeaud insisted that the border be demarcated along the Muluwiya River, a position further west than the Tafna River which Morocco considered to be the border.

The war began on August 6, 1844, when a French fleet under the command of the Prince de Joinville conducted a naval bombardment of the city of Tangiers. The conflict peaked on August 14, 1844 at the Battle of Isly, which took place near Oujda. A large Moroccan force led by the sultan’s son Sīdī Mohammed was defeated by a smaller French imperial force under Marshal Bugeaud. Essaouira, Morocco’s main Atlantic trade port, was attacked in the Bombardment of Mogador and briefly occupied by Joinville on August 16, 1844.

The war was formally ended on September 10, with the signing of the Treaty of Tangiers, in which Morocco agreed to arrest and outlaw Abd al-Qādir, reduce the size of its garrison at Oujda, and establish a commission to demarcate the border. (The border, which is essentially the modern border between Morocco and Algeria, was agreed in the Treaty of Lalla Maghnia.)

Sultan Abd al-Rahman’s agreement to these terms, which amounted to a capitulation to French demands, threw Morocco into chaos, with Alawī and other tribal areas threatening secession in support of Abd al-Qādir, and calls in some circles for al-Rahman to be deposed in favor of Abd al-Qādir. The sultan and his sons eventually regained control over the sultanate, and were able to marginalize Abd al-Qādir’s calls for jihad by pointing out that without their support, Abd al-Qādir was not a mujahid, or holy warrior, but merely a mufsid, or rebel. By 1847 the sultan’s forces were in jihad against Abd al-Qādir, who surrendered to French forces in December 1847.

Second Franco-Moroccan Wars

French artillery at Rabat in 1911

The Secon Franco-Moroccan War, or French conquest of Morocco, took place in 1911 in the aftermath of the Agadir Crisis, when Moroccan forces besieged the French-occupied city of Fez. Approximately one month later, French forces brought the siege to an end. On 30 March 1912, Sultan Abdelhafid signed the Treaty of Fez, formally ceding Moroccan sovereignty to France, which established a protectorate. On 17 April 1912, Moroccan infantrymen mutinied in the French garrison in Fez. The Moroccans were unable to take the city and were defeated by a French relief force. In late May 1912, Moroccan forces unsuccessfully attacked the enhanced French garrison at Fez. The last aftermath of the conquest of Morocco occurred in September 1912 when French colonial forces under Colonel Mangin defeated Moroccan resistance at the Battle of Sidi Bou Othman.

Flag of Alaouite dynasty

Flag of Alaouite dynasty

Flag of Alaouite dynasty used in the 19th Century